441 South Harbaugh Street

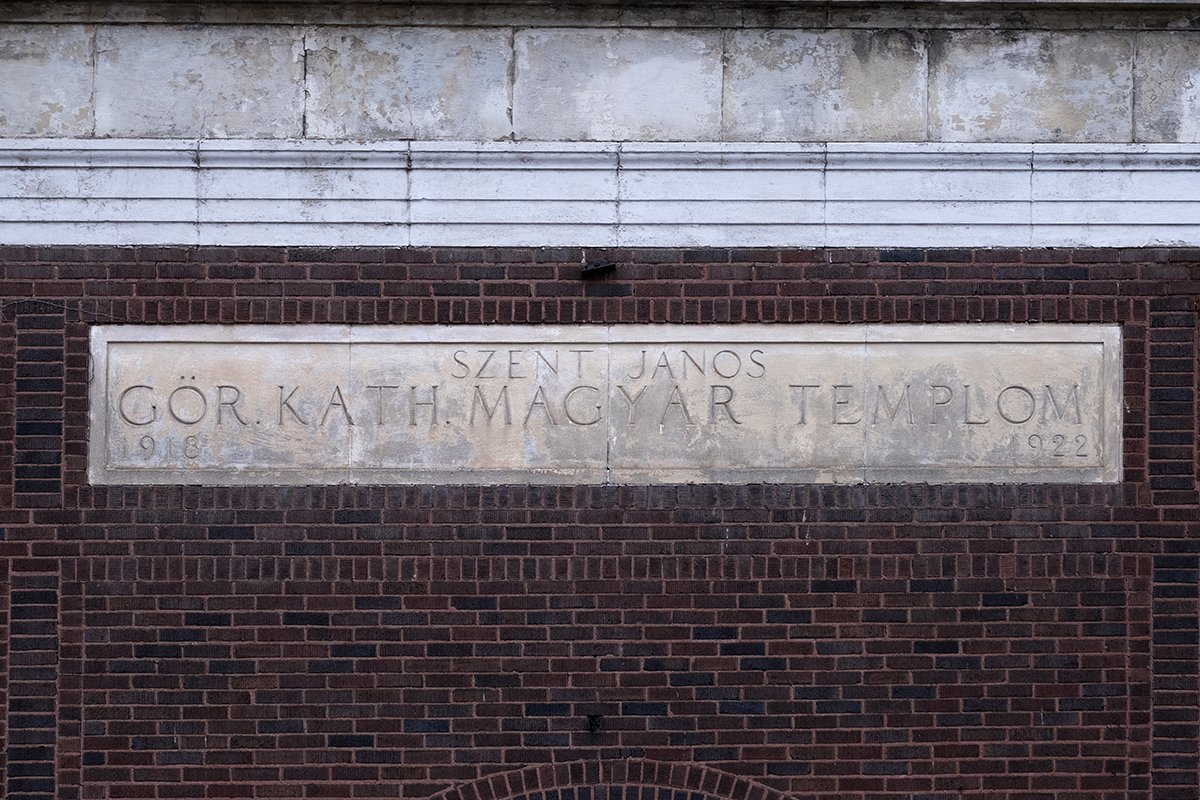

Szent Janos Görög Katolikus Magyar Templom, Saint John Greek Catholic Hungarian Church, St. John The Baptist Byzantine Catholic Church, Jehovah Jireh Full Gospel Church

Industry bolstered Delray’s population around the turn of the century. Operations like the Solvay Process Company and Michigan Malleable Iron Company brought in thousands of immigrants, many of whom emigrated from Hungary.

A plurality of these Hungarians practiced catholicism, so a need for new churches soon presented itself. Holy Cross Catholic Church was founded in May 1905, and its first structure was completed a year later. A block down South Street, another congregation was formed in 1915 by Reverend Edmund Volkay.

This new congregation would start building a church around 1917 and would take five years to be completed. Szent Janos Görög Katolikus Magyar Templom, which translates to Saint John Greek Catholic Hungarian Church and is pictured here, opened in 1922. A quarter-mile down South Street, Holy Cross opened its present structure in 1925. On one end of the block, Szent Janos catered to the Greek Catholic Hungarians, and on the opposite side, Holy Cross served the Roman Catholics.

Back in 1906, the corner of Harbaugh and South had been platted for homes and smaller structures, but none had been built yet. Because of this, the temple is surrounded by residential homes, which creates a unique neighborhood feel that resembles those you’d see in Europe.

The new church was designed by Henrick Kohner and saw many pastors in the early years. After Edmund Volkay left, Balint Balogh, Peter Popovits, Anton Knapik, Joseph Kovalcsik, John Ludach, Eugene Kapisinsky, and Method Goydich ran the church. Reverend Goydich, who had been there for nine years, passed away in 1939 at 57. He was born in Budapest and lived in the attached rectory. Shortly after, Father Louis Artim took over.

In 1940, Szent Janos celebrated its 25th anniversary. More than 2,000 were expected to partake in the festivities, and important Hungarian Greek Catholics from across the midwest were in attendance.

In 1943, there was an advertisement in the Detroit Free Press that made me chuckle. Father Louis Artim wrote, “Who would be willing to send a Father, who is collecting U.S. stamps, those stamps of which he has two?” and included his address, which was the church’s attached rectory.

By the 1960s, the church had changed its name to St. John The Baptist Byzantine Catholic Church. It was the same congregation; from my understanding, a Byzantine Catholic Church is the same or very similar to a Greek Catholic Church. By this point, Delray was no longer the Hungarian stronghold it once was, but the church continued catering to the Hungarians left in the area. In 1966, the congregation celebrated its 50th anniversary with a Golden Jubilee. To commemorate the occasion, Nicholas T. Elko, the reverend from Pittsburgh, spoke.

Throughout the 1970s, most of the mentions of the church that I’ve found are in obituaries. This era was characterized by two things for Delray: population loss and heavy industrialization. The City of Detroit decided Delray would become one of the state’s most industrialized and polluted neighborhoods. Before doing this, they didn’t ask residents what they thought or offer them an arm to leave the neighborhood if they wanted to.

Similar to the 1890s, new industrial sites meant new jobs, albeit on a smaller scale. However, contrary to what happened at the turn of the century, the advent of the automobile made it easy to commute to work from afar, Delray had little to no investment from the city for schools and parks, and the public’s knowledge about the health effects of living near these factories was higher. Citizens of Delray were abandoned by their city in favor of the taxes brought in by large corporations that were killing their neighbors with pollution. If they could help it, people who worked at these factories didn’t live in Delray.

A nonprofit corporation called the Catholic Church of St. John The Baptist Byzantine Rite was incorporated in 1962 and was dissolved in 1981 at the address of Szent Janos. For some time, the reverend was Doctor Bela S. Nyika. I’ve been digging for quite some time to find information about Szent Janos in the 1970s and 1980s without much avail.

However, I did find a piece on the last pastor, Reverend Vegvari. The Reverend, or Basil as he was known then, was born in Hungary around 1929. By 1956, he helped run a Franciscan Boys’ School 45 miles west of Budapest. By this point, the Hungarian Uprising (sometimes called the Hungarian Revolution) had started to take hold. Against the orders of his superintendent, Vegvari walked 45 miles to Budapest to fight against the USSR.

When he arrived, Soviet troops soon took the city, and Vegvari was in the heat of the action. Older than most of the university students that surrounded him, he was one of the leaders. When Soviet Troops bombarded their hideout, the group dispersed, and the priest headed out on foot to reach the Austrian border. When he arrived, an older woman led him and other young men through a minefield to freedom.

Peter Gavrilovich told this story in the Detroit Free Press in October 1986. In the piece, Gavrilovich states that the church was soon to be sold. Apart from that, it didn’t offer much information; however, it did say that Basil Vegvari would go home. Hungary was his home, and he planned to go back there, one way or another.

I’m unsure if the church was sold in 1986 or when Szent Janos closed its doors for good. My best guess is that it closed in the late 1980s. By 1996 the structure had been sold to Jehovah Jireh Full Gospel, a non-denominational church run by Bishop Phillip Pulliam. Founded as Harbour Light Mission Non-Denominational Church in 1973, the parish was renamed Jehovah Jireh Community Church, Non-Denominational in 1987 and again in 1996 to take the current name.

In July 2012, the Michigan Chronicle reported that Bishop Pulliam was one of the few locals hoping for the new bridge to Canada to be placed in Delray. Then in his 80s, he worried that he would soon be unable to care for the church anymore. When the Gordie Howe Bridge plans were announced, Pulliam was disappointed that his church was not in the footprint, meaning he wouldn’t get a payout for demolition.

The article says that only a few members were still attending the church. Due to the skyrocketing costs of maintaining a church in a historic building nobody was coming to anymore, Pulliam chose to close the church for good. His health required a live-in nurse and daily physical therapy sessions—he was in no state to care for the Szent Janos building.

The church had folded by 2013. Bishop Phillip Pulliam died on June 1, 2018, at 88.

Since then, the church has fallen harshly into disrepair. The ornate painted ceiling has started to crumble, and the interior has been smashed up and painted by urban explorers and vandals.

Today, the ownership of the structure has become muddy. It may have been purchased, but foreclosure documents were drawn up in 2021 against Pulliam’s former church. That same year, the stained glass windows were taken. Some say they are being preserved, but I fear they were sold.

The first few years after it became vacant, the neighbors did what they could to protect Szent Janos. However, there’s only so much they can do. After multiple break-ins, the structure is almost certainly going to be demolished. The neighborhood continues to lose population, the pollution hasn’t improved, and the city pretends people don’t live in Delray.

It would take a miracle to save the former home of Szent Janos Görög Katolikus Magyar Templom. Still, the memories remain. This is important, as Basil Vegvari said when speaking about Hungary in 1986, “…to keep ourselves remembering, and reminding others.”

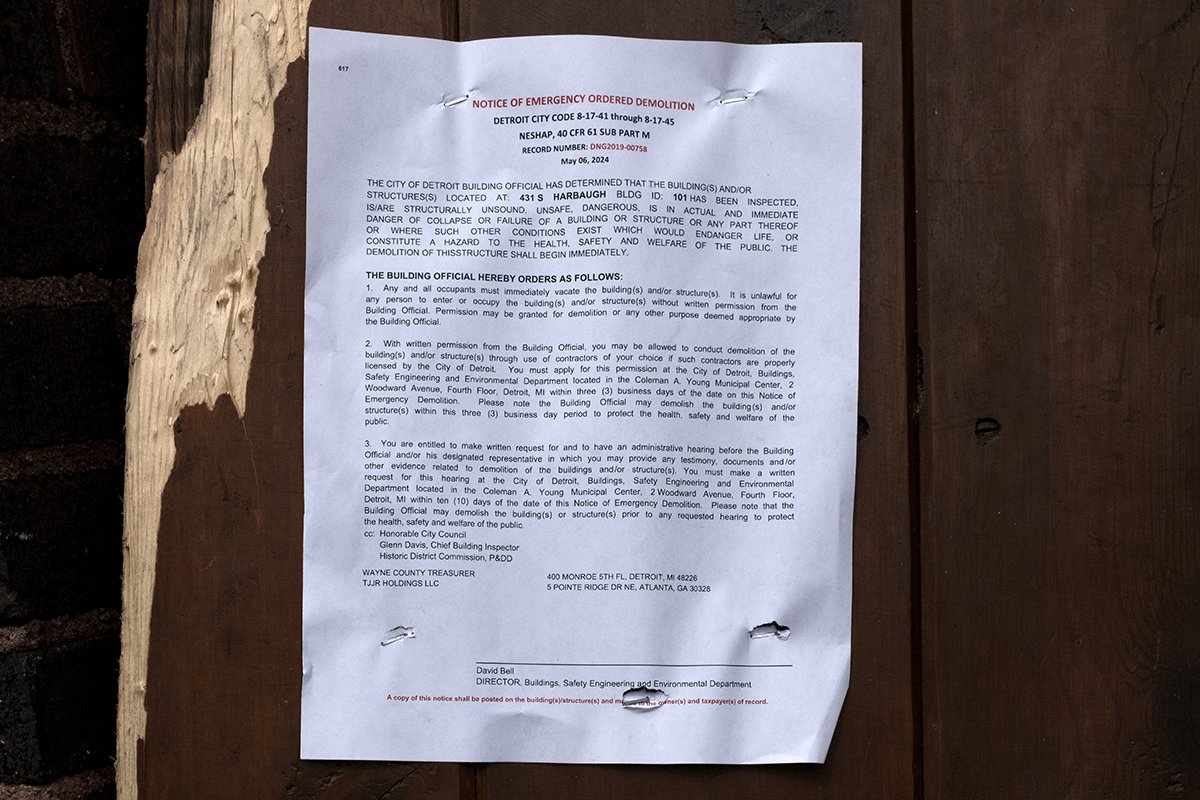

May 6, 2024 Update

The Spring of 2024 was the beginning of the end for Szent Janos Görög Katolikus Magyar Templom.

Around April 21st, 2024, the rectory next door was set ablaze. Luckily, the fire was mostly contained to that structure, and there wasn’t significant damage to the church, which is much more architecturally significant. A week later, around April 28, another fire occurred at the rectory and in the church’s basement. Though the main floor of the sanctuary was mostly spared from damage, destruction continued to creep closer to its still intact painted ceilings. Perhaps if someone stepped in to secure the structure, it could have been saved. Unfortunately, Szent Janos wasn’t given that opportunity.

Security camera footage shared with me by a neighbor shows an explosion blasting outside the windows and doors of the church at 4:30 AM on May 5, 2024. Initial reports said the fire was caused by a natural gas leak, which makes sense after seeing the video. It is doubtful that the church still had an active gas line, so the leak was likely caused by a faulty line elsewhere that allowed gas to seep into the basement of the church. Though that may indicate what fueled the fire, it doesn’t say what ignited it. With no electricity or gas hookup, it’s hard to know what caused the church to blow. Regardless, DTE should have to answer to folks asking how this happened.

Knowing that the structure had already been damaged by fire, Detroit Fire Fighters attempted to contain the blaze, but not much more, as it was in danger of collapsing, and the structure had been vacant for more than ten years. The church was left in dire shape; however, the building didn’t collapse. The roof mostly came down, but the structure was still standing.

On the evening of May 5th, that same day, the church was on fire again. Likely a reflash, Detroit firefighters were again on the scene to extinguish the blaze. Though much more tame than a few hours earlier, the structure continued to fall into absolute destruction.

On Monday, May 6th, I went to see Szent Janos before work. No one was around except for a neighbor sitting on his porch staring up at the crumbling steeple—or so I thought. I began documenting the structure, as I assumed demolition crews would show up at any moment. Then, I noticed that the steeple was still smoking. Tiny flakes of smoldering ash fell onto the sidewalk below, albeit infrequently.

Right at that moment, a Detroit Police Officer came around the corner. I flagged him down and told him that it was still smoking and that hot ashes were falling from the steeple, to which he replied, ‘Don’t worry, they know,’ with a smile, then did something with his radio. We spoke briefly, and he darted off, turning left on Dearborn Street.

I continued documenting the building and heard a scraping noise, like a piece of steel was teetering on the edge of falling off. I assumed it was damage from the fire, so I continued taking photos. There was no basement anymore, well, not really. The structure had entirely collapsed and was a tangled mess of concrete, rebar, steel, and charred wood. While fighting the blaze, water filled the basement and had to be pumped out.

While taking a photo through one of the windows, I noticed a man wading through the wreckage inside. He had a snapback on his head, a pair of dirty jeans, a cigarette behind his left ear, and a tattered high-vis vest on. Even with the reflective outer layer, no one had any business going inside this church, as it could have collapsed at any moment. This was a very dedicated scrapper.

Though I’ve already painted a picture of this man’s appearance, I haven’t mentioned the first thing I noticed about him. In addition to a small piece of metal that appeared to have come from a window frame, he was carrying a half-drunk two-liter bottle of Faygo Cola. Though I couldn’t imagine going inside this structure in its current state, I had to agree with his choice of Faygo flavors. We made eye contact, nodded, and both went about our business.

As I was finishing up with the photos I wanted to take before heading to work, I came around the corner at the same time as the scrapper. He introduced himself to me, and we talked for a while. He said he was into the history of these old buildings but didn’t hesitate to jump on the opportunity to scrap them when they burnt. He said he’d often watch demolition teams bring them down without getting any of the metal inside because the exterior was structurally unsafe or there wasn’t enough metal inside to make it worthwhile. I’m unsure if that actually happens, but he was passionate about it.

My first thought was that this was who started the fire. However, I don’t think he would have gone out of his way to talk to me if that was the case, and he let me snap a portrait of him inside, too, which seems odd to do if you were the one who started the fire. Still, it was a strange but insightful interaction.

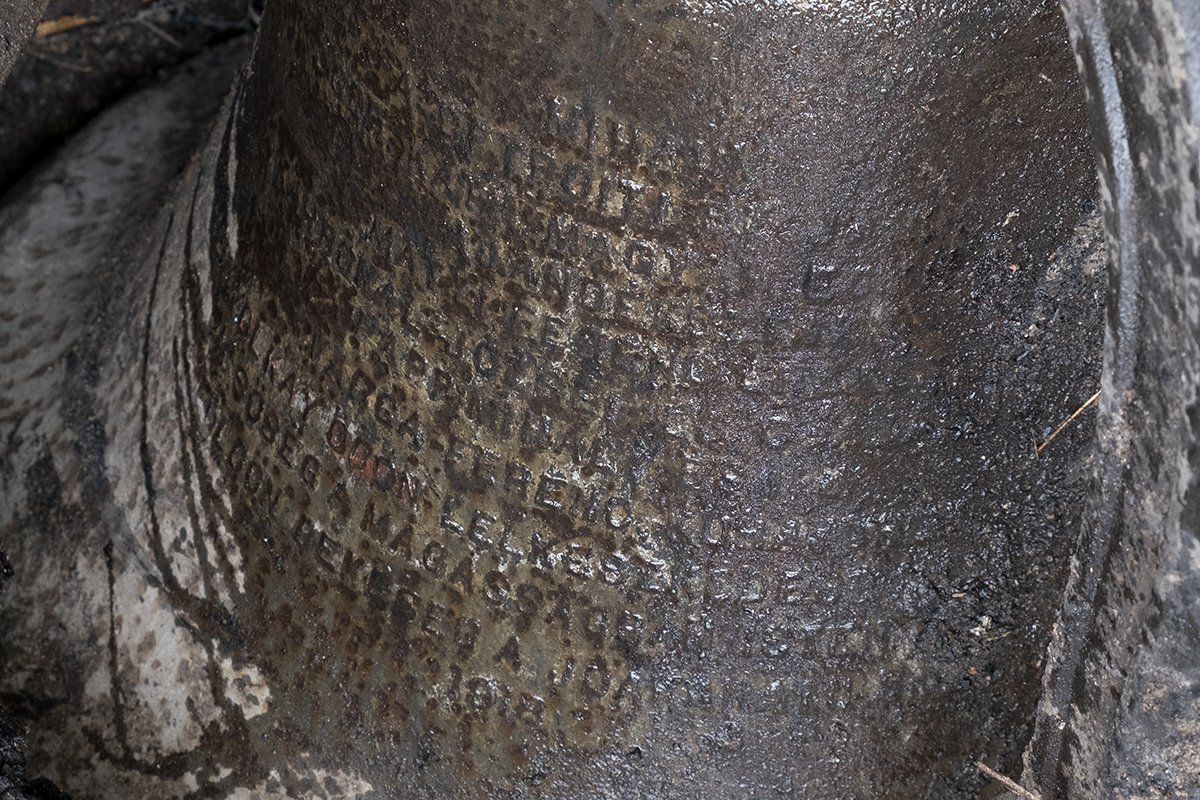

The first time I documented Szent Janos Görög Katolikus Magyar Templom in-depth, roughly a year prior, I photographed the church bells atop the steeple. On this visit, one of the bells was mixed in with the rubble in the middle of the Church’s front door. Likely weighing hundreds of pounds, it fell straight down during the blaze, like a child’s toy that had fallen out of favor for something newer and flashier, albeit with a much louder thud. Also in the doorway were tattered pieces of copper roofing from the steeple. While talking with the scrapper, he made quick work of those.

May 7, 2024

The next day, I returned for another visit to see if demolition crews had shown up. There wasn’t any machinery, but things were a bit different. There was a red condemnation flyer on the structure, and at some point, a white paper explaining that the structure was slated for an emergency demolition had been stapled to the tattered remains on the door. The smaller church bell I saw on my first visit was gone, and, according to a neighbor, the Detroit Fire Department had returned and taken it that Monday. One of the larger bells was now visible, peaking out from the rubble.

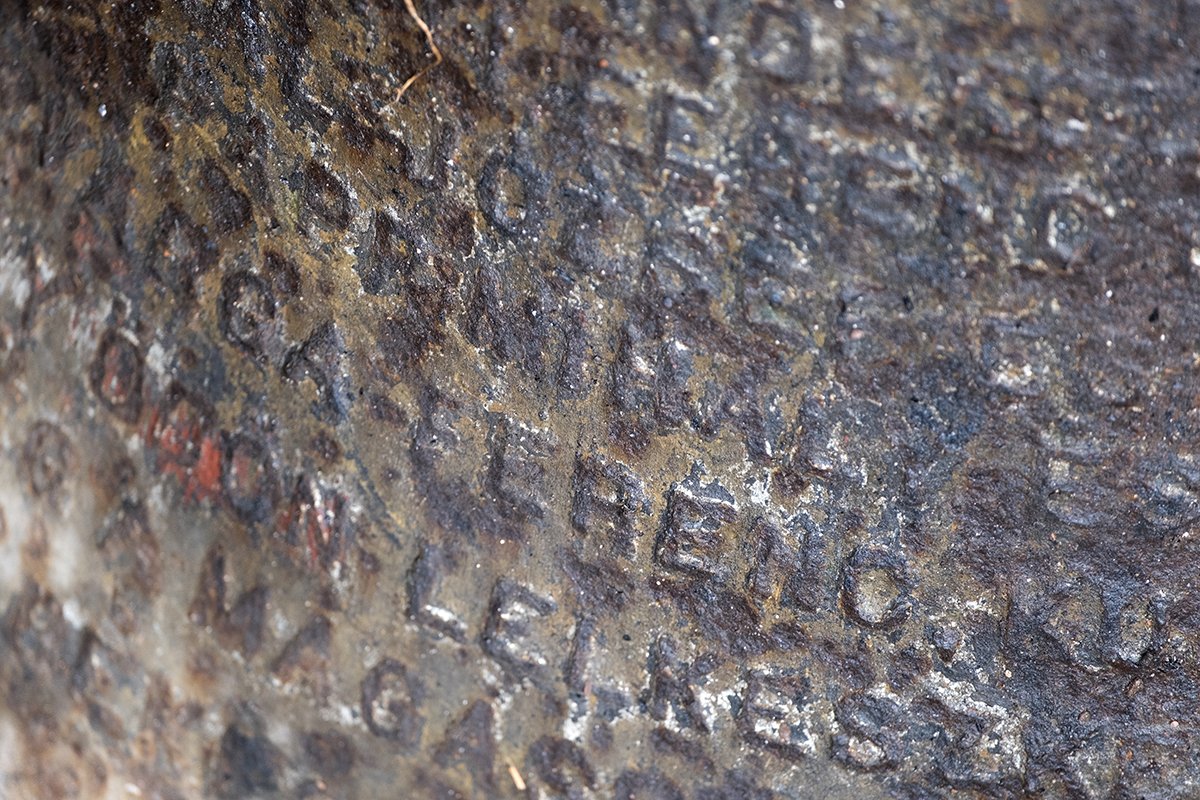

Detroit artist Scott Hocking had cleared some of the materials on top of it and cleaned it off, and there was an inscription in Hungarian on the iron exterior of the bell. Scott estimates that it weighs around 1000 pounds. Initially, there were at least three bells in the central tower. There may have been additional bells in the towers on the left and right sides. One of the smaller ones was allegedly taken by the Detroit Fire Department, another one is mixed inside the rubble, and another one is still in the central tower, visible from the circle opening atop the church’s facade, as Scott pointed out.

On my second visit, the same man I saw gathering metals was there again. He still had his two liter of Faygo Cola and was haning out inside the church. He remembered me, and we spoke for a few minutes before he walked down Harbaugh Street and out of sight. Multiple people stopped in their cars to chat and talk about the church. It was clear that many of them were driving by to say goodbye.

Though it hasn’t happened yet, I don’t see a world where Szent Janos isn’t demolished in the coming days. In most other parts of the city, it would have been demolished already. However, in Delray, there are fewer stakeholders that the city wants to keep happy, so it might take a while for them to get to it. It’s unlikely that the owners will fight the emergency demolition, and I don’t blame them. There’s little to salvage here after the fire. Hopefully, the bricks and steel can be repurposed, and the bells can be saved, cleaned, and reused.

No matter what, this marks the end of an era for Delray. Szent Janos Görög Katolikus Magyar Templom was an institution for decades, and Jehovah Jireh Full Gospel took over that torch in the 1990s until Bishop Phillip Pulliam’s health deteriorated, forcing the church to close for good.

On May 7, I filed a Freedom Of Information Act Request with the City of Detroit to try and get the fire reports on this structure to put the cause of the fire in this piece. My request may have been premature, as a fire investigation would likely take weeks. Still, I figured I could always submit another one later. Initially, I’m hoping to learn about the first fires in April. When or if I hear back, I will update the post.

Though this feels like goodbye, I can’t imagine I won’t revisit this structure in the coming weeks.

Bell Update (May 11, 2024)

The Detroit Fire Department took the first bell on May 6, 2024. A few days later, volunteers from the Detroit BSEED office came to retrieve the other one. They’re working with the Byzantine Rite Church to find a permanent home for the bells. I suggested to those in contact with the church that the bells should stay in Delray; however, I’m not sure how well that was received. They may attempt to get the third bell, which is still up in the cupola, when demolition occurs.

Demolition Update (May 30, 2024)

A demolition fence was erected around Szent Janos on Thursday, May 30. I spoke with demolition crews Thursday morning, and they said that the plan was to start work bringing down the century-plus-old church on Friday (May 31). However, they are waiting on DTE to move a few power lines for demolition, so it may be pushed until Monday or Tuesday if they can’t get crews out here fast enough.

As I’ve covered, two of the church’s bells were recovered, one by the Detroit Fire Department and another by Detroit’s BSEED Office. One remains in the cupola, and I was told that demolition crews would try and retrieve it. However, none of the crew I spoke with knew anything about that. If they didn’t on Thursday morning, they absolutely did after talking with me.

My Freedom of Information Act Request submitted on May 7 inquiring into the fire was extended by the City of Detroit until May 30 (today). However, I’m still waiting on an email from the City of Detroit Law Department.

By the end of next week, Szent Janos will likely be unrecognizable or gone completely. I hope that the Adamo demolition crews are able to save the last bell and that one of the three finds a permanent home somewhere in Delray, not in the suburbs. It belongs in Delray.

Demolition Update (June 5, 2024)

On June 4th, DTE crews removed powerlines that were in the way of wrecking crews tearing down the structure. Early the next morning, Adamo workers began dismantling the rectory, followed by the rear portion of the church. By midday, all of the church structure except the front portion with the bell tower had been brought down. Around 4 PM, crews were still picking up the rubble they had torn down earlier. They told me they needed different equipment to bring down the taller front portion and that they’d start early the following day, June 6th.

Using a telephoto lens, I determined that the last bell was still in the cupola. Nobody on the crew seemed to know anything about it, but I told them what I knew. Local4 News was on the scene reporting about the demolition, too, and I told reporter Shawn Ley about the history of the structure and the bells. None of that history made it into the news at 6 PM, but he did mention the last bell in the tower.

More info and photos to come soon.

Soon, there won’t be much left of the old Delray except writings from former residents in online forums and the engraved names on tombstones.

It’s important to remember what happened here because, if we don’t, it’s bound to happen again.

The address is also listed as 431 South Harbaugh.