2000 East Canfield Street

St. Albertus Parochial School

Every time this happens, I tell myself I shouldn’t be surprised. That said, here I am, surprised again. But we’ll get to that later.

St. Albertus Parish was founded in 1871 and was Detroit’s first Polish Roman Catholic Church. The modern church was completed in 1885 and has been a staple of the east side and Polish Detroit for nearly a century and a half.

The first St. Albertus School was located on the parcel where the church is today. It was a wooden structure, so it wasn’t a lasting solution. The second school, a three-story brick structure with twelve school rooms and a large hall on the upper floors, was dedicated on May 21, 1893. The building cost about $40,000, which parishioners funded.

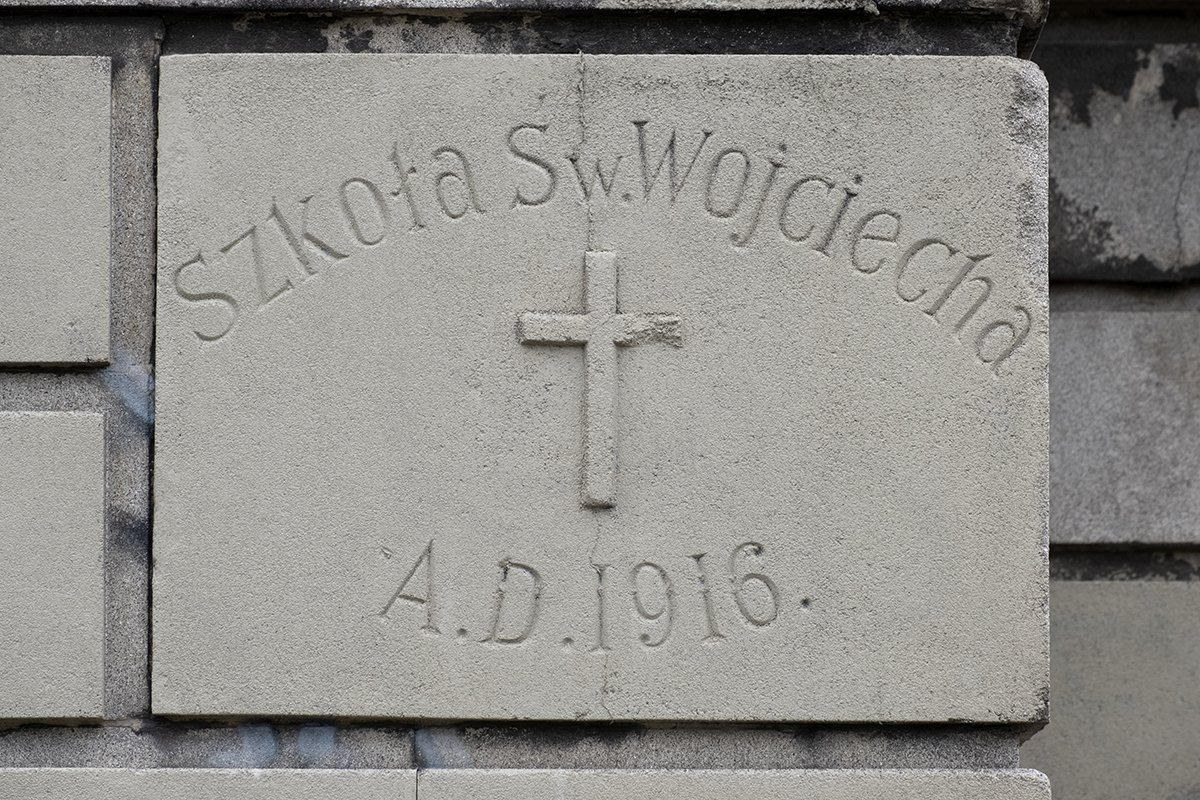

Detroit’s Polish population boomed in the first two decades of the 20th century, and a new school building was required. Work began behind the church on October 4, 1916, and the new school was dedicated on September 30, 1917, less than a year later. Bishop Edward D. Kelly of Detroit and Father Michael Grupa, the president of the Orchard Lake Polish Seminary, spoke at the ceremony.

Harry J. Rill was given the nod as architect, and the school had 24 classrooms and eight large meeting rooms. Additionally, there was a reading room, library, large billiard room, and specialty classrooms for domestic science and manual training. The All Season Top Company used the old school building to manufacture automobile rooves. By 1922, the company was bankrupt, and the structure was later demolished.

The school was the center of life for Poles in Detroit for decades. Classes were taught in Polish, and many immigrants learned to speak English at the school. Felician Sisters ran it. Students sang in the choir at midnight mass on Christmas, played on St. Albertus sports teams, and participated in after-school programs at the church.

In 1948, part of the upper school was utilized as a temporary reception center for the arrival of displaced Europeans because of the war. Americans could apply to have their relatives located and brought to the States. After the war ended, more Poles landed in Detroit, but many had started moving to the suburbs. That said, St. Albertus was still going strong.

In 1953, a pupil at St. Albertus was killed nearby in an event that sparked change around the city. Robert ‘Bobby’ Drewek, 13, was a safety patrol boy at the intersection of Canfield with the Grand Trunk Rail Line west of the school. His mother had died a few years prior, so he lived with his sister. He got to his post at 8 AM and helped ensure students got across the railroad safely. The crossing had lights and an arm that came down, but these devices weren’t as reliable as today. They were still operated by a person pressing a button.

After escorting a group of classmates across the tracks, Bobby noticed the Grand Trunk Commuter flying down the tracks. Simultaneously, he saw a car approaching the intersection and ran into the road to alert the driver. The car sped past him and was hit by the train, pushing the automobile backward, striking and killing young Bobby Drewek. Shortly after the accident, the safety arms and lights were initiated. The driver was hospitalized but survived.

This was the second accident in a week at the crossing, the first of which had prompted a GT repairman to try and fix the safety features. The gatekeeper, John Kaczmarek, 61, blamed faulty machinery after he was investigated for manslaughter. Later testing showed that it took at least 6 seconds after pressing the button for the safety features to be initiated, which was far too long. Additionally, city officials noted that trains often sped faster than the 30-mile-per-hour speed limit that was common at the time. It was a foggy morning, and GT officials said that the locomotive was going just 20 miles per hour at the time of the accident.

They-mayor Albert Cobo planned an all-day conference with other city officials to try and remedy the issue. In the end, improving the warning devices and enforcing speed limits for trains were recommended. At the time, there were 268 railroad crossings in Detroit. Officials planned to find twenty high-risk intersections, including where Robert Drewek was killed, and remedy issues there first. The 100 Club (now the 200 Club), an organization that assists the families of fallen police officers and firefighters, paid for his funeral. After all, he died serving his community. In the end, his life was taken as the result of a lack of investment in infrastructure.

In the 1950s, the Polish community became a beacon of freedom for Poles escaping war and looking for a stable living was starting to show signs of instability. For decades, Polish immigrants and first-generation Americans could exist within a few square blocks. You could have your first communion, graduate from high school, get married, and find an affordable house, all within a short walk of St Aubin and Canfield. As Poles left Detroit and the city started to change, this wasn’t an opportunity for young Detroiters of any ethnic descent.

The school was closed around 1966 but was still used by the church for various community events and uses. In 1971, it was used as a polling place for the Citizens’ Governing Board and Health Council of the Model Neighborhood. After that, I’m not confident in what capacity it was used. The church continued to operate until 1990, when the Archdiocese of Detroit closed it and dozens of other parishes.

The Polish American Historic Site Association was incorporated in 1992 by Christine Biestek, Michael Krolewski, and Dolores Cetlinski. Eventually, the nonprofit took over the church property, including the school. They continued to maintain the church and school buildings to the best of their abilities; however, the church was the focal point of their project. Eventually, the school was sold to fund renovation efforts at the church.

Today, the church is still operational. There are a handful of masses here every year, sometimes in English, Polish, and Latin. The space is also available for weddings and can be rented for just about any purpose.

I’m unsure who the nonprofit sold the school to initially. However, we’ve reached the point in this article where I reveal what shouldn’t have surprised me but always does. The school is currently owned by Grand Lofts, LLC, an operation owned and run by Dennis Kefallinos.

Between Dennis and his son, Julian, the Kefallinos family owns a lot of property in Poletown East. Although this is technically Forest Park or McDougall-Hunt, it always felt like an extension of Poletown.

An interesting tidbit about this property is how it’s taxed and how that would change under the new Land Value Tax Plan proposed by the city. According to the parcel map, the school property’s taxable value is just $11,100 for a whopping 35,384 square feet. That’s a rate of 0.3137 dollars per square foot. In contrast, a structure still in use at the corner of Willis and St Aubin nearby is just 12,022 square feet but has a taxable value of $105,900. Per my made-up metric, that’s 8.81 dollars per square foot.

Under the new Land Value Tax Plan, taxes will be increased on abandoned buildings, parking lots, and scrapyards so that taxes for homeowners can be lowered. I’ll admit that I know very little about tax law, but that seems like a good move to me. Maybe if the tax bill gets significantly higher, negligent owners like Kefallinos will sell properties to be redeveloped rather than get taxed at a higher rate to sit on them. Kefallinos owns some operational structures, which will lower his tax bill, but I believe it will still negatively affect his portfolio.

All that said, I’m not holding my breath for Kefallinos to sell all his properties anytime soon, as he claimed he was doing in 2017. This structure is a fifteen-minute walk from Eastern Market and roughly a mile from Woodward Avenue and Midtown. The neighborhood already has some density because of the apartments and townhomes across St Aubin Street, making the idea of a mixed-use development all the more promising. Plus, with the Joe Louis Greenway under construction, a 27.5-mile cycling and walking trail will be located a stone’s throw away from the school. Redevelopment isn’t just possible; it makes a lot of sense.

With that, I’ll get off my soapbox. What would you want to see this structure turned into?