3433 East Warren Avenue

Marathon Linen Supply Company, Marathon Linen Service

This structure includes 3429, 3431, and 3433 East Warren Avenue

The Marathon Linen Supply Company was established in 1927 on the state level. It was to be a full-service commercial laundry operation and lease linens to businesses and for special events. The company was founded by Nicholas and George Genematas, two brothers who immigrated from Greece. On the original paperwork, Nicholas was president, with 3,751 shares; George was Vice President and Treasurer, with 3,748 shares; and Steve Mandalis was Secretary, with one share. The company started with $75,000 in capital.

Despite that paperwork, I believe the company was founded before going legit with the state. George’s obituary stated that he founded the company in 1905, and there’s a piece in the Detroit Free Press about an attempted robbery at the Marathon Linen Service on Howard Street in 1925, two years before the company filed its articles of incorporation on the state level.

I’m not sure when the structure pictured here was built, but I’m sure it was built over time. Initially, I believe it was a small, single-story building on the corner of Warren and Moran. Eventually, the operation moved upwards and outwards to meet the needs of the expanding linen service, which would eventually change its name to Marathon Linen Service and operate under the Martex, Inc. name, too.

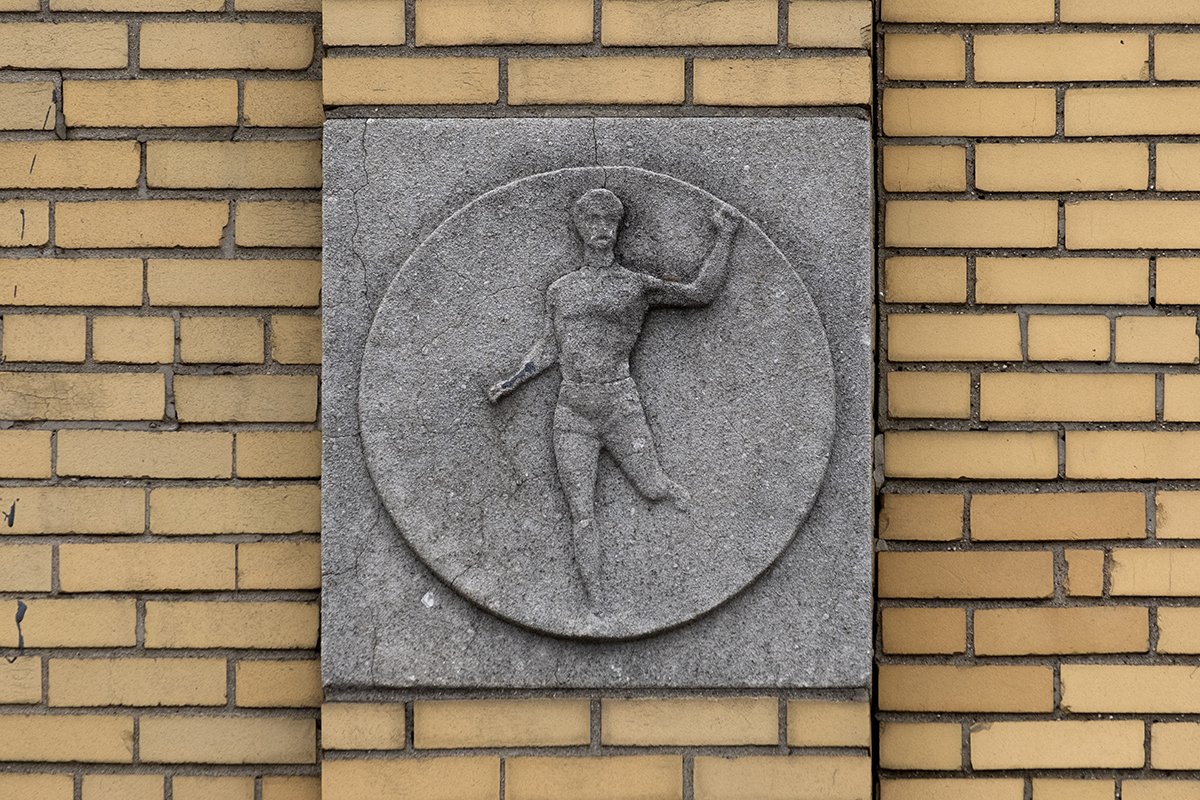

Looking at the structure today, it’s easy to miss the ornate details on the facade. The bars on the windows are unique, and the brickwork at the top of the structure catches your eye, but there are ornate pieces on both sides of the building. They depict a man who appears to be running or doing some sort of physical activity. I think that this might be Pheidippides, the character that was said to have inspired the modern marathon race by running 150 miles from Marathon to Athens. Considering the name of the company, this adds up. Hopefully, someone reading this knows more about Greek Mythology and can tell me more! There are a few places where the ornamental details were replaced with cinder blocks, and I’m curious if there was something more ornate there.

By 1934, Nicholas, who went by Nick, was running the business. In July, he started receiving calls from criminals who claimed that they were going to kill him and bomb the plant pictured here if he didn’t pay them $1,000. Genematas phoned the police, and Inspector John Hoffman in the Special Investigation Squad hatched a plan. He sent Detective Seargent Adam Shriner and Detective John Davies to Genematis’ office to implement it.

On Monday, July 16, the officers sat waiting in Nick’s office at the plant. When the extortionists called, Nick answered, instructing the men to come to the plant to get the money. When they arrived, he gave them $400 in marked bills the police had provided him. As the men were leaving, the two officers came out of hiding and cuffed them, taking them to jail.

In August, the nightwatchman at the plant was doing his rounds and noticed that a second-floor window had been busted, so he phoned the police. Thieves had broken into the large safe and stolen a smaller safe from inside it. The police had no leads. However, a few days later, the safe was discovered under a bundle of clothing in an abandoned laundry truck at Field and Hendrie. Police thought the robbers may have gotten spooked by a DPD scout car, fleeing on foot.

Despite those instances, Detroit’s east side wasn’t all doom and gloom in the 1930s. Generally, it appears that Marathon Linen was a good place to work. The plant had a bowling team that would play other companies across Detroit. In 1936, 165 Marathon Linen employees received bonuses ranging between $5 and $25 in addition to a holiday turkey for Christmas. In 2024, that’s between $110 and $550.

The bowling leagues continued into the 1940s, and the plant would soon unionize. The company was constantly hiring in the 1940s, which wasn’t terribly uncommon as the war made work unpredictable, and after Japan’s surrender, the United States saw shocking growth and celebration. Odds are, a lot of fancy events that commemorated the end of the war used leased linens from Marathon.

However, in 1944, inflation was still a worry for Americans. Marathon was penalized for paying their workers too much, which wasn’t terribly uncommon. The federal government had placed restrictions on how quickly businesses could up pay, as they were worried about inflation hitting the country again. Marathon was fined $5,400, and seven other Detroit businesses were fined, too. Because firms couldn’t raise worker pay, finding people for hard labor jobs was challenging. This led to more businesses offering benefits and health insurance in an attempt to bring workers into their company.

In the 1940s, Nicholas Genematas moved to Arizona. I’m unsure if he was still involved with the business. George remained in the Detroit area.

A few times in the 1950s, the Marathon-Bryant Linen Service is mentioned. It doesn’t appear that the company changed names, so I’m not certain of the reasoning for that.

On November 6, 1951, George Genematas, one of the company’s founders, was killed in a car crash near Port Huron. His funeral was four days later, on a Saturday, and the offices and plant were closed to honor his legacy. I assume employees were meant to go to his funeral.

In 1953, the Marathon Linen Service placed an advert in the paper alongside the Bryant Linen Service and Service Linnel Supply Company. They said they had been pestered by a group of Detroit linen supply companies to join a trade alliance to raise and fix customer prices, essentially killing the free market. The advert said, “Whereas these inducements sound legitimate on the surface, they actually represent coercion and force to close the linen supply market in Metropolitan Detroit,” and asked for the public’s support. I’m curious if the Bryant Linen Service was the reason for mentioning the Marathon-Bryant company.

In 1967, Nicholas Genematas died in Arizona. He was 78. His obituary said that he came to the United States in 1914 and had recently commissioned a sculpture to be made of Hippocrates for the Wayne State School of Medicine. According to WSU, the statue was unveiled in 1971.

Throughout the late 1980s and 1990s, the Marathon Linen Company was consistently in the Detroit Free Press’ Significant Industrial Pollutant Violators Public Notice Bulletin. They failed to submit a 6-month wastewater analysis, exceeded the maximum pH level, didn’t complete forms correctly, and other things. Despite that, the company continued to operate and was hiring reasonably frequently. Adverts said the company had good benefits, health care, and 401K contributions. The ads stopped around 2002.

The company was still filing on the state level until 2009 and was dissolved in 2010. Looking at Google Street View, I’d guess that the structure was vacated before that.

Online listings show that the property is owned by Commodity Resources Incorporated, a company founded in 2002 by Gregory Wierszewski and dissolved in 2017. I’m not certain if he still holds the property or if it’s in limbo. A quick search shows that Wierszewski runs Richmond Recycling, a scrap yard. This makes sense, as two cars look ready to take to the yard out back of the structure pictured here, and another vehicle can be seen through a broken window. The one inside might have been someone’s project at one time, but it’s been stripped by thieves and graffiti artists, who have had their way with this structure over the past decade and a half.

The bones of the main structure look okay, but the secondary building on the Moran side has seen better days. The roof has failed, though you can still see steel beams supporting the structure. I imagine this building needs heavy remediation after decades of use as a laundry facility. A sign out back indicates that there are tanks under the parking lot, too.

The need for remediation is probably how it landed in the hands of a scrap yard owner and may be why it’s still standing. To demolish a property like this correctly is costly, so, like old gas stations, they tend to sit for ages until the state steps in or somebody wants the land bad enough to clean it or cap it with concrete. Considering it’s located within Poletown East, a neighborhood that still receives little to no investment from the city, I’d imagine that this structure will continue to sit here until it deteriorates in a more noticeable way.

After taking these photographs, a young man approached me on the sidewalk. Despite being soft-spoken, he had a lot to say, and I enjoyed our conversation. We talked about the neighborhood, race, discrimination, Black Bottom, the world, and his family. He said that his dad and uncles had worked at Marathon and, despite never seeing it open, that he would be sad if they tore it down. JD and I had to talk for 20 minutes, and I hope to run into him again while taking photos in the neighborhood.

I can’t help but agree with JD that it’ll be a sad day when the Marathon Linen Building comes down. I don’t know when that’ll be, but East Warren will never be the same when it finally does.

What would you turn it into if you had unlimited cash with the stipulation that you could only use it to fix up this building?